A CONVERSATION BETWEEN VICTOR LAVALLE & LISA MORTON

Photo of Lisa Morton by Seth Ryan; photo of Victor LaVallle by Teddy Wolff

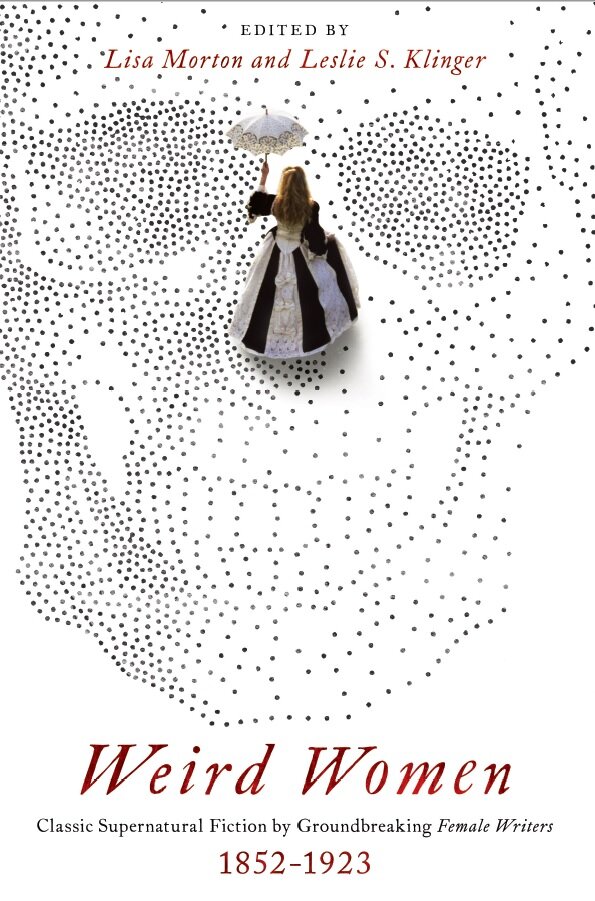

VICTOR: Lisa, your story in Weird Tales, “A Housekeeper’s Revenge,” feels so wonderfully of the moment in its theme but still managed to have a real human connection at the heart of it. How did you work on that balance?

LISA: First of all, Victor, coming from a writer whose work I admire as much as yours, I take that as a high compliment indeed, so thank you!

When I first started to think about writing a story in the Weird Tales style, I knew immediately that I wanted to flip some tropes. Cults have been big lately in mass media (hmmm...I’m sure that has nothing to do with current politics), so I decided to take the typical idea of a cult being made up of barbarous savages and turn them into one-percenters; who, after all, would be more willing to sell out the world in order to retain power? After that, I thought about the protagonist – who would take on the elite? I have a dear friend who came to this country from El Salvador as a child, and she’s made her living as a cleaner. I know how some of her clients dismiss and disrespect her (I’ve personally witnessed it on one occasion), and it makes me very angry (as it does her). I knew I wanted to use that anger and some of my friend’s characteristics, so that all went into my heroine.

Speaking of that Weird Tales style...one of the things I love about your work, Victor, is the way you manage to both drag weird fiction kicking and screaming out of the shadows of the twentieth century, and yet approach it with a genuine fondness (sidebar moment: in “Up From Slavery”, you actually describe my very first Lovecraft book, that Ballantine/Del Rey paperback of At the Mountains of Madness!). When and how did you first encounter weird fiction, and what was your immediate reaction to it?

VICTOR: I am just as honored by the compliment. Thank you, Lisa! And I love knowing that extra/off the page information about the inspiration for your story. That sense of affection for your friend comes through clearly to me. And I’ll bet your friend has an even deeper, more personal reaction to seeing herself there. Side note, one I’d love to discuss later in this thread, is how you manage/choose to keep the personal/real world people and their details and how you also go on to protect the privacy of those who have inspired some part of the text.

As for weird fiction, I’m willing to believe I didn’t know it when I first encountered it. Or maybe I mean to say I didn’t recognize it as a kind of fiction, the weird. I’m specifically thinking of comic books, the Dr. Strange comics done by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Even more than the stories, I tend to credit Ditko’s art as my introduction to the weird. I’m thinking of a particularly famous panel when Dr. Strange is fighting an entity named Eternity. The character of Eternity is the outline of a figure wearing a kind of headpiece and flowing robes (on the arms). So it’s a recognizable silhouette, but inside the figure is the cosmos. Stars and planets float inside Eternity. The being has half a face but only half (in this panel). It was such a brilliant way to embody the idea of eternity/the cosmic while not reducing it into to something as mundane as the human scale. I could understand, but not relate. I think that’s the right way to say it. Again, I didn’t think any of this consciously, but felt it stirring some less world-bound imagination in me. I was fascinated though I can’t say I loved it. I wanted to try and grasp it though. Maybe that was my true first reaction to the weird, if this example counts. It made me curious.

Do you remember your first encounter with the weird? In literature? In life?

LISA: Whoa – I also vividly remember that mind-blowing Steve Ditko art! A few years later, my mind was equally blown by the art Frank Brunner provided for a Dr. Strange reboot.

My childhood probably had its own shades of cosmic weirdness, thanks to my dad – he was a mad genius-engineer who worked on projects like designing the helmets for the Mercury space program. In terms of the arts, I think my first real introduction to weird fiction, though, was when a cousin sent me a boxed paperback set of Lovecraft (which included that aforementioned copy of At the Mountains of Madness). I was probably about 14 or 15; I’d already read one Lovecraft story in a school book, but it was “The Outsider”, not a Mythos tale. I was pretty astonished by the stories in those books; I’d never read anything like them. They were both horrific and awe-inspiring...and of course at 14 you’re more willing to overlook the sometimes bloated prose. I started trying to find out more about Lovecraft, and that led me to others of his circle like Robert E. Howard. I kept seeing this name Weird Tales referenced, but this was back in the 1970s, when the magazine was not being published, so I had only a vague idea of what it was like.

Even as a younger reader, though, I sensed there was...welll...something wrong with Lovecraft’s worldview. His eldritch gods were always in league with “swarthy foreigners”; and of course women were all but absent in his work. At the time I wasn’t yet giving serious thought to pursuing a writing career, but I think the desire to read weird fiction with other characters was always sitting in the back of my head.

What was your experience of encountering Lovecraft’s work like? When did you first start thinking about riffing on his work?

VICTOR: Wait a second. I do want to get to that Lovecraft question, but I can’t just gloss over this aside you tossed off. “...he was a mad genius-engineer who worked on projects like designing the helmets for the Mercury space program.”

Uhhh. More, please! Of course, I totally understand if you don’t want to, or like to, discuss but I leaned in so hard when I saw that line, I practically cracked my computer screen. I’m interested in what he was doing, of course – and the specificity of designing the helmets – but I’m even more interested in what it’s like to be the child, to be you in those circumstances.

I bring this up because I’m thinking of my mother. She was an immigrant from Uganda, fleeing the murderous regime of Idi Amin, and she settled in New York City. She eventually found work as a secretary and that’s the job she did for most of her life. That was how she made money, but the way she found happiness is that on the weekend she made art. My mother drew, sculpted, sang and played a piano. A genuinely creative person, and simply for the pleasure of it, the release. She never tried to sell the things she made, I don’t think it would even have occurred to her. But I was there, watching. I was learning the most important lesson from her: creativity is an act of pleasure. It was a fun thing to do with your time. That lesson – unintended but certainly there – has remained with me all my life. And it’s been a balm at those times when I felt careerist, underappreciated, poorly paid (if being paid at all); the times when I’ve felt like a failure, it has been my mother’s example that raised my spirits again and got me back to the writing.

Did I just go down a strange avenue? Did your father (or mother) and their lives inspire or steer you toward writing in any way? I promise, I’ll steer back to the Lovecraft in the next exchange, but I’m genuinely curious about this, if you’re open to discussing it.

LISA: Your mother sounds like a remarkable person, and I think I can say that she and my dad shared a similar love of creating. My dad was really a one-of-a-kind guy – he was a lanky, amiable Hoosier (think Jimmy Stewart) who walked away from his family’s multi-million-dollar printing business to move to California and design stuff. What’s funny to me now is that as a child, he wasn’t around much and I really thought my mom was the dominant parent, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve realized that I’m definitely my father’s daughter. He always worked as an independent contractor, so we moved a lot; as an only child, that left me spending a lot of time making stories up to entertain myself. When we lived in L.A., he worked with the Air Force out of Edwards Air Force Base and was always bringing home crazy stuff like space capsule models and helmets (I’ve even got this great photo of me as a toddler wearing a prototype helmet). Weirdly, he never liked to talk about his work much, although maybe he couldn’t; it wasn’t until after he passed away in 2015 that I found out he’d actually carried the rank of Captain in the USAF, but had been discharged under somewhat mysterious circumstances. After he left the Air Force, he worked on things like the development of the liquid crystal (I was the first kid with a digital calculator from Texas Instruments!) and PCs. He always preferred to talk about his obsession with hunting and fishing, and that’s a whole other part of my childhood that was somewhat bizarre – he’d drag me out of school every October to haul Mom and I off to Idaho or Montana or something so he could shoot Bambi while we shivered in a camper. I guess you could say I grew up surrounded by tech on one hand and blood on the other!

Did your mother approve of your writing? My mom read some of mine, but she got too freaked out by it. My dad wasn’t a fiction reader, but one of the best days of my life was when, a few months before he died, he read my novel Netherworld and called me at work to tell me how much he loved it.

VICTOR: “Tech on one hand and blood on the other!” What a great summary of a life. And that picture of you in the helmet is adorable and also quite badass. I’m grateful you were willing to talk about those aspects of your life. Thank you for sharing it. I love the story of your father getting to tell you how much he enjoyed your novel. That must have felt like such a lightning bolt of love and understanding. That’s a gift for any writer.

My mother neither approves or disapproves of my writing. She doesn’t read much of it and I’m actually pretty happy about that. She’s an immigrant, as I stated earlier, so for her the great happiness she feels is that I got a good education, I have a good job that helps me take care of my kids, that I’m married to a good woman with her own good job. Her dream for me was, and still is, security. Not really all that different from many parents, I would guess. So the writing, for her, is something that makes me happy and by getting published I’m making a little more money than I would if I didn’t publish so she has nothing but good feelings about my writing now.

This wasn’t always the case. When I was younger, and less thoughtful, I published a first novel that was extremely autobiographical (a Black guy from Queens, fails out of college, moves home to live with his mother, grandmother, and sister). The mother and grandmother are both immigrants from Uganda. I’m telling you I didn’t make up much! That part wouldn’t have been so bad, but I did include our family history with mental illness. Three generations of family members dealing with schizophrenia, bipolar, clinical depression. It was a lot. And to make things worse, I didn’t hide who the family members were all that well. This hurt my mother a lot. Of course, wrapped in with the revelation of mental illness is the stigma of personal shame. If these had been stories I put in a journal, I don’t think she would’ve cared. (And she wouldn’t ever have seen them, most likely.) But once they’re published, they become something else. They become public. And now one may worry about the opinions of extended family, neighbors and friends. Anyway, I learned my lesson after that. To be more respectful of other people’s privacy. To write about the things that matter to me but, hopefully, to do them in a way that isn’t meant to expose or hurt others. (And there was an undercurrent of anger, resentment, in that novel though I couldn’t see it, or wouldn’t, at the time.)

And right after that I started writing books with monsters in them! One of the gifts of doing so – of diving right into horror, my first literary love – was that I found I could write more honestly about myself, my family, than I ever could when I was being strictly autobiographical. And yet, I also could give myself enough distance to tell a story, one that didn’t require the reader to know or care about my personal connection in any way. It felt like I got to put everything into the work, which was a revelation.

So you mentioned knowing there was something off about Lovecraft and his worldview, so were you drawn to other “weird” authors? If so, whose magic worked on you?

LISA: You know, I enjoyed other weird authors like Howard and Clark Ashton Smith, but the first author I really fell madly head-over-heels in love with wasn’t a weird fiction writer, but rather a science fiction writer: Theodore Sturgeon. I discovered him via two episodes of the original Star Trek that he wrote, and his work was packed with not just magnificent ideas and lovely prose, but also deeply human characters. This was before I was even old enough to drive, so my mom would indulge me with occasional visits to used bookstores, where I’d spend my allowance on old beat-up paperbacks of Sturgeon’s work. I will say that although he was mostly known as a science fiction author, he also wrote the all-time best non-supernatural vampire book, Some of Your Blood. I still wish someone would adapt that and his classic More Than Human into film.