Weird Tales Announces Major Deal With Blackstone!

Weird Tales announces major deal with Blackstone!

We are proud to let everyone know that we are now partners with Blackstone Publishing!

Together we will be making novels and anthologies under the “Weird Tales Presents” imprint, and releasing digital and audio versions of the magazine.

We are proud to let everyone know that we are now partners with Blackstone Publishing!

Together we will be making novels and anthologies under the “Weird Tales Presents” imprint, and releasing digital and audio versions of the magazine.

Full details below:

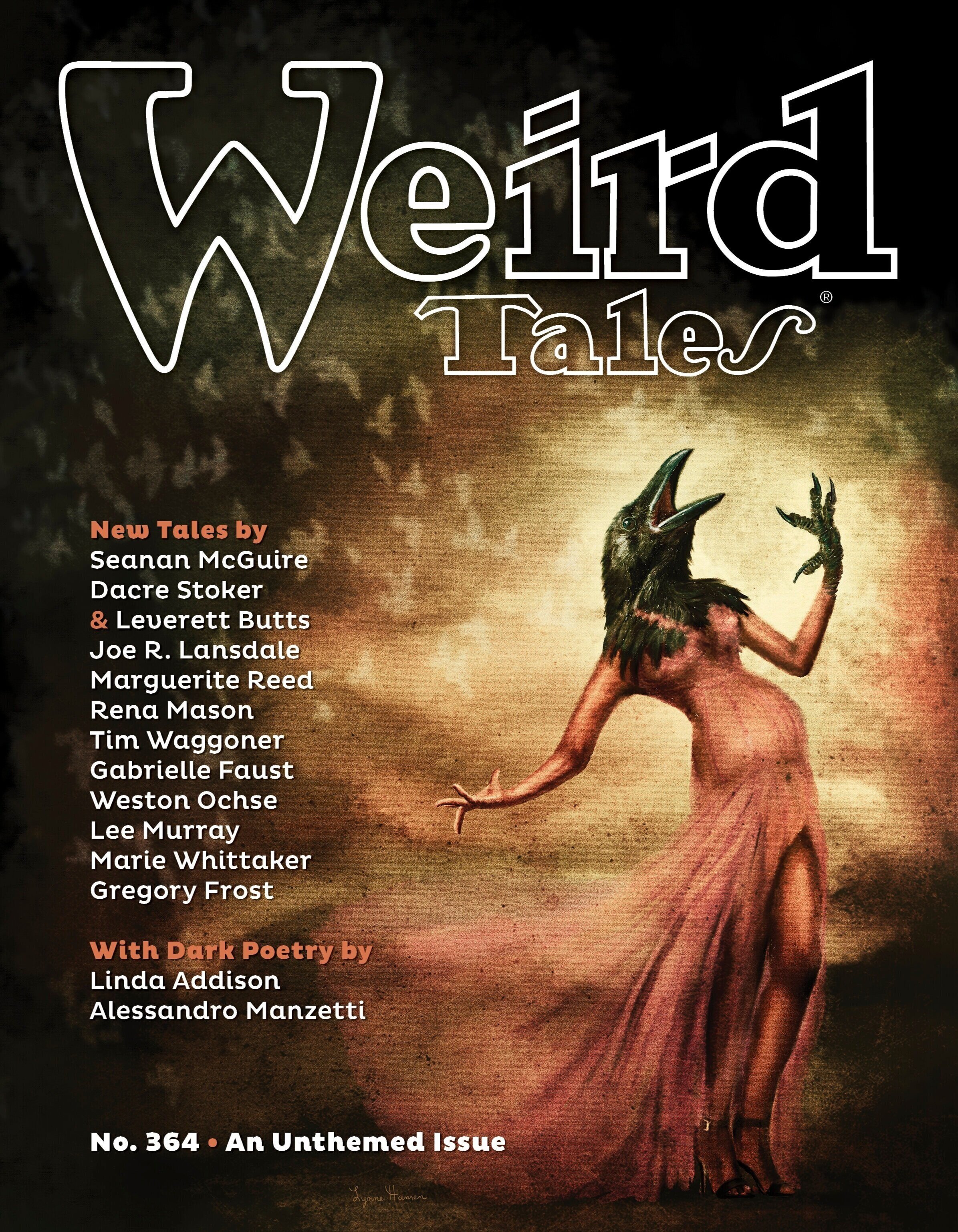

ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST: Lynne Hansen

Lynne Hansen illustrated the cover for Issue #364

This issue’s cover was created by horror artist Lynne Hansen.

“I was so excited to be asked to create cover art for Weird Tales,” Hansen said, “but with 363 other covers before mine, the pressure was on! I wanted to do something that honored the 97-year grand pulp tradition of the magazine, but also felt contemporary. Using Tim Waggoner’s story ‘Feathers’ as a jumping off point, I chose a pregnant African American woman as the main character. I named the piece ‘Becoming’ — a reference to the transformation of the woman, myself as an artist, and Weird Tales itself.“

Lynne Hansen specializes in book covers and her clients include Cemetery Dance Publications, Thunderstorm Books and Raw Dog Screaming Press. Her art has been commissioned and collected throughout the United States and overseas. In 2021, Art-Haus Gallery in Atlanta, Georgia will host her solo art show “Lyrical Nightmares: The Art of Lynne Hansen.”

You can find her on the web at LynneHansenArt.com and at @LynneHansenArt on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

INTERVIEW: Sean Patrick O’Reilly

By James Aquilone | Weird Tales talks with the writer, director and producer of the Howard Lovecraft animated movies.

By James Aquilone

Sean Patrick O'Reilly has been one of the most prolific animation producers in recent years. As the owner and operator of Arcana Studio, which is also Canada's largest comic book company, he’s produced nine feature films – including the Howard Lovecraft trilogy (Howard Lovecraft and the Frozen Kingdom, Howard Lovecraft and the Undersea Kingdom & Howard Lovecraft and the Kingdom of Madness). Recently he took a break from moviemaking to return to his comic book roots and created a Christmas tale with artist David Alvarez.

Randolph the Reindeer, available now, follows an ex-hotshot reindeer who must brave a deadly snowstorm to reach Santa's workshop to replace a beloved family heirloom before a family’s Christmas is ruined forever.

I recently got to talk to Sean about the book as well as plans for other Lovecraftian stories.

JAMES AQUILONE: Why did you write Randolph the Reindeer?

SEAN PATRICK O’REILLY: I’ve always loved the stories that are kind of personal and simple. Shows like Breaking Bad and Ozark, where there are personal struggles. You’re not saving the world. There’s no Thanos to overcome. You don’t need the Infinity Gauntlet. It’s an intimate, simple story, and at Christmas it always feels like the one thing that people have is saving Christmas. So the idea of Randolph was there was Rudolph, who was obviously the winner, he saves Christmas, he’s the hero — and to every yin there’s a yang, and Randolph was not that. He’s kind of a loser. He did not make Santa’s sleigh. He’s not the winner, but years later he gets a redemption.

JA: Was there an inspiration for Randolph?

SPO: Randolph would be kind of like Chris Elliot — mid-40s, had the best years of his life behind him. He’s happy-go-lucky but at the same time he can turn on a dime and have a sad story to tell.

JA: You’ve produced a ton of animated movies. Do you have plans for a Randolph movie?

SPO: What I would love is that sometime between now and February we try to set up a Randolph live-action version for Christmas 2021. If it’s animated, it takes me two to three years, but if it’s live action we can shoot it in a month. I am thinking about it. I definitely want to do it. I already have two versions of a script based on Randolph.

JA: You’ve written, directed and produced the animated Howard Lovecraft trilogy. Are they any more Howard Lovecraft movies in the works?

SPO: I don’t have any plans for any additional Howard Lovecraft movies. However, I did do a four- to five-minute short film [for a TV series]. It’s two different scenes and it’s called Miskatonic. We played it at Comic-Con this year. We had a virtual panel. After the movies, Howard gets invited to Miskatonic University. The tagline I’ve been using is “Somewhere between Harvard and Hogwarts is Miskatonic.” Howard goes there to learn more about Lovecraftian magic. I wrote the pilot. I have the bible for the series. It’s the best animation we’ve done. It’s really high end. We’re pitching it now to studios.

JA: In your bio you say you took Arcana Studio from a one-person operation in your basement to an award-winning comic book publisher and then to an animation studio. How did you do that?

SPO: Slowly. To print a comic book, a floppy 32-page, it costs around $3500. I did Kade #1. I remember paying $3500, which was a ton of money, and I got my money back. And I was quite happy. I did issue two and I got my money. I did issue three and I got my money back. Then I did a new series called Ant. It went crazy on eBay. Copies were selling for $100. We were red hot and I realized that there was not much money in comics. At the end of the day, we put in our pocket maybe $5000. At that point the economics of it shifted our business a little bit more to film and television. Now we have 65 people working from home. Our salaries are $100,000 a week. Five grand is about the amount we spend per month on toilet paper and soap. The economics have complete changed.

All three of the HOWARD LOVECRAFT films are available on Amazon Prime Video as well as through Shout! Factory. For more about Sean and Arcana’s comic book line, go to ArcanaComics.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James Aquilone was raised on Saturday morning cartoons, comic books, sitcoms, and Cap'n Crunch. Amid the Cold War, he dreamed of being a jet fighter pilot but decided against the military life after realizing it would require him to wake up early. He had further illusions of being a stand-up comedian, until a traumatic experience on stage forced him to seek a college education. Brief stints as an alternative rock singer/guitarist and child model also proved unsuccessful. Today he battles a severe chess addiction while trying to write in the speculative fiction game.

His first novel, DEAD JACK AND THE PANDEMONIUM DEVICE, has been optioned for film and TV. His short fiction has been published in such places as Nature's Futures, The Best of Galaxy's Edge 2013-2014, Unidentified Funny Objects 4, and Weird Tales Magazine. He lives in Staten Island, New York, with his wonderful wife. Sign up for his newsletter here: http://eepurl.com/bx5axT or visit DeadJack.com.

A CONVERSATION BETWEEN VICTOR LAVALLE & LISA MORTON

Weird Tales contributors Victor LaValle & Lisa Morton chat about their work, weird fiction and much more.

Photo of Lisa Morton by Seth Ryan; photo of Victor LaVallle by Teddy Wolff

VICTOR: Lisa, your story in Weird Tales, “A Housekeeper’s Revenge,” feels so wonderfully of the moment in its theme but still managed to have a real human connection at the heart of it. How did you work on that balance?

LISA: First of all, Victor, coming from a writer whose work I admire as much as yours, I take that as a high compliment indeed, so thank you!

When I first started to think about writing a story in the Weird Tales style, I knew immediately that I wanted to flip some tropes. Cults have been big lately in mass media (hmmm...I’m sure that has nothing to do with current politics), so I decided to take the typical idea of a cult being made up of barbarous savages and turn them into one-percenters; who, after all, would be more willing to sell out the world in order to retain power? After that, I thought about the protagonist – who would take on the elite? I have a dear friend who came to this country from El Salvador as a child, and she’s made her living as a cleaner. I know how some of her clients dismiss and disrespect her (I’ve personally witnessed it on one occasion), and it makes me very angry (as it does her). I knew I wanted to use that anger and some of my friend’s characteristics, so that all went into my heroine.

Speaking of that Weird Tales style...one of the things I love about your work, Victor, is the way you manage to both drag weird fiction kicking and screaming out of the shadows of the twentieth century, and yet approach it with a genuine fondness (sidebar moment: in “Up From Slavery”, you actually describe my very first Lovecraft book, that Ballantine/Del Rey paperback of At the Mountains of Madness!). When and how did you first encounter weird fiction, and what was your immediate reaction to it?

VICTOR: I am just as honored by the compliment. Thank you, Lisa! And I love knowing that extra/off the page information about the inspiration for your story. That sense of affection for your friend comes through clearly to me. And I’ll bet your friend has an even deeper, more personal reaction to seeing herself there. Side note, one I’d love to discuss later in this thread, is how you manage/choose to keep the personal/real world people and their details and how you also go on to protect the privacy of those who have inspired some part of the text.

As for weird fiction, I’m willing to believe I didn’t know it when I first encountered it. Or maybe I mean to say I didn’t recognize it as a kind of fiction, the weird. I’m specifically thinking of comic books, the Dr. Strange comics done by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Even more than the stories, I tend to credit Ditko’s art as my introduction to the weird. I’m thinking of a particularly famous panel when Dr. Strange is fighting an entity named Eternity. The character of Eternity is the outline of a figure wearing a kind of headpiece and flowing robes (on the arms). So it’s a recognizable silhouette, but inside the figure is the cosmos. Stars and planets float inside Eternity. The being has half a face but only half (in this panel). It was such a brilliant way to embody the idea of eternity/the cosmic while not reducing it into to something as mundane as the human scale. I could understand, but not relate. I think that’s the right way to say it. Again, I didn’t think any of this consciously, but felt it stirring some less world-bound imagination in me. I was fascinated though I can’t say I loved it. I wanted to try and grasp it though. Maybe that was my true first reaction to the weird, if this example counts. It made me curious.

Do you remember your first encounter with the weird? In literature? In life?

LISA: Whoa – I also vividly remember that mind-blowing Steve Ditko art! A few years later, my mind was equally blown by the art Frank Brunner provided for a Dr. Strange reboot.

My childhood probably had its own shades of cosmic weirdness, thanks to my dad – he was a mad genius-engineer who worked on projects like designing the helmets for the Mercury space program. In terms of the arts, I think my first real introduction to weird fiction, though, was when a cousin sent me a boxed paperback set of Lovecraft (which included that aforementioned copy of At the Mountains of Madness). I was probably about 14 or 15; I’d already read one Lovecraft story in a school book, but it was “The Outsider”, not a Mythos tale. I was pretty astonished by the stories in those books; I’d never read anything like them. They were both horrific and awe-inspiring...and of course at 14 you’re more willing to overlook the sometimes bloated prose. I started trying to find out more about Lovecraft, and that led me to others of his circle like Robert E. Howard. I kept seeing this name Weird Tales referenced, but this was back in the 1970s, when the magazine was not being published, so I had only a vague idea of what it was like.

Even as a younger reader, though, I sensed there was...welll...something wrong with Lovecraft’s worldview. His eldritch gods were always in league with “swarthy foreigners”; and of course women were all but absent in his work. At the time I wasn’t yet giving serious thought to pursuing a writing career, but I think the desire to read weird fiction with other characters was always sitting in the back of my head.

What was your experience of encountering Lovecraft’s work like? When did you first start thinking about riffing on his work?

VICTOR: Wait a second. I do want to get to that Lovecraft question, but I can’t just gloss over this aside you tossed off. “...he was a mad genius-engineer who worked on projects like designing the helmets for the Mercury space program.”

Uhhh. More, please! Of course, I totally understand if you don’t want to, or like to, discuss but I leaned in so hard when I saw that line, I practically cracked my computer screen. I’m interested in what he was doing, of course – and the specificity of designing the helmets – but I’m even more interested in what it’s like to be the child, to be you in those circumstances.

I bring this up because I’m thinking of my mother. She was an immigrant from Uganda, fleeing the murderous regime of Idi Amin, and she settled in New York City. She eventually found work as a secretary and that’s the job she did for most of her life. That was how she made money, but the way she found happiness is that on the weekend she made art. My mother drew, sculpted, sang and played a piano. A genuinely creative person, and simply for the pleasure of it, the release. She never tried to sell the things she made, I don’t think it would even have occurred to her. But I was there, watching. I was learning the most important lesson from her: creativity is an act of pleasure. It was a fun thing to do with your time. That lesson – unintended but certainly there – has remained with me all my life. And it’s been a balm at those times when I felt careerist, underappreciated, poorly paid (if being paid at all); the times when I’ve felt like a failure, it has been my mother’s example that raised my spirits again and got me back to the writing.

Did I just go down a strange avenue? Did your father (or mother) and their lives inspire or steer you toward writing in any way? I promise, I’ll steer back to the Lovecraft in the next exchange, but I’m genuinely curious about this, if you’re open to discussing it.

LISA: Your mother sounds like a remarkable person, and I think I can say that she and my dad shared a similar love of creating. My dad was really a one-of-a-kind guy – he was a lanky, amiable Hoosier (think Jimmy Stewart) who walked away from his family’s multi-million-dollar printing business to move to California and design stuff. What’s funny to me now is that as a child, he wasn’t around much and I really thought my mom was the dominant parent, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve realized that I’m definitely my father’s daughter. He always worked as an independent contractor, so we moved a lot; as an only child, that left me spending a lot of time making stories up to entertain myself. When we lived in L.A., he worked with the Air Force out of Edwards Air Force Base and was always bringing home crazy stuff like space capsule models and helmets (I’ve even got this great photo of me as a toddler wearing a prototype helmet). Weirdly, he never liked to talk about his work much, although maybe he couldn’t; it wasn’t until after he passed away in 2015 that I found out he’d actually carried the rank of Captain in the USAF, but had been discharged under somewhat mysterious circumstances. After he left the Air Force, he worked on things like the development of the liquid crystal (I was the first kid with a digital calculator from Texas Instruments!) and PCs. He always preferred to talk about his obsession with hunting and fishing, and that’s a whole other part of my childhood that was somewhat bizarre – he’d drag me out of school every October to haul Mom and I off to Idaho or Montana or something so he could shoot Bambi while we shivered in a camper. I guess you could say I grew up surrounded by tech on one hand and blood on the other!

Did your mother approve of your writing? My mom read some of mine, but she got too freaked out by it. My dad wasn’t a fiction reader, but one of the best days of my life was when, a few months before he died, he read my novel Netherworld and called me at work to tell me how much he loved it.

VICTOR: “Tech on one hand and blood on the other!” What a great summary of a life. And that picture of you in the helmet is adorable and also quite badass. I’m grateful you were willing to talk about those aspects of your life. Thank you for sharing it. I love the story of your father getting to tell you how much he enjoyed your novel. That must have felt like such a lightning bolt of love and understanding. That’s a gift for any writer.

My mother neither approves or disapproves of my writing. She doesn’t read much of it and I’m actually pretty happy about that. She’s an immigrant, as I stated earlier, so for her the great happiness she feels is that I got a good education, I have a good job that helps me take care of my kids, that I’m married to a good woman with her own good job. Her dream for me was, and still is, security. Not really all that different from many parents, I would guess. So the writing, for her, is something that makes me happy and by getting published I’m making a little more money than I would if I didn’t publish so she has nothing but good feelings about my writing now.

This wasn’t always the case. When I was younger, and less thoughtful, I published a first novel that was extremely autobiographical (a Black guy from Queens, fails out of college, moves home to live with his mother, grandmother, and sister). The mother and grandmother are both immigrants from Uganda. I’m telling you I didn’t make up much! That part wouldn’t have been so bad, but I did include our family history with mental illness. Three generations of family members dealing with schizophrenia, bipolar, clinical depression. It was a lot. And to make things worse, I didn’t hide who the family members were all that well. This hurt my mother a lot. Of course, wrapped in with the revelation of mental illness is the stigma of personal shame. If these had been stories I put in a journal, I don’t think she would’ve cared. (And she wouldn’t ever have seen them, most likely.) But once they’re published, they become something else. They become public. And now one may worry about the opinions of extended family, neighbors and friends. Anyway, I learned my lesson after that. To be more respectful of other people’s privacy. To write about the things that matter to me but, hopefully, to do them in a way that isn’t meant to expose or hurt others. (And there was an undercurrent of anger, resentment, in that novel though I couldn’t see it, or wouldn’t, at the time.)

And right after that I started writing books with monsters in them! One of the gifts of doing so – of diving right into horror, my first literary love – was that I found I could write more honestly about myself, my family, than I ever could when I was being strictly autobiographical. And yet, I also could give myself enough distance to tell a story, one that didn’t require the reader to know or care about my personal connection in any way. It felt like I got to put everything into the work, which was a revelation.

So you mentioned knowing there was something off about Lovecraft and his worldview, so were you drawn to other “weird” authors? If so, whose magic worked on you?

LISA: You know, I enjoyed other weird authors like Howard and Clark Ashton Smith, but the first author I really fell madly head-over-heels in love with wasn’t a weird fiction writer, but rather a science fiction writer: Theodore Sturgeon. I discovered him via two episodes of the original Star Trek that he wrote, and his work was packed with not just magnificent ideas and lovely prose, but also deeply human characters. This was before I was even old enough to drive, so my mom would indulge me with occasional visits to used bookstores, where I’d spend my allowance on old beat-up paperbacks of Sturgeon’s work. I will say that although he was mostly known as a science fiction author, he also wrote the all-time best non-supernatural vampire book, Some of Your Blood. I still wish someone would adapt that and his classic More Than Human into film.

INTERVIEW: Rena Mason

By L. Marie Wood | Weird Tales talks with Rena Mason, whose story “To the Marrow” will appear in issue #364.

By L. Marie Wood

I had the pleasure of speaking with accomplished dark speculative fiction author and Bram Stoker Award® winner Rena Mason about her experiences in the genre, her influences, and her thoughts on Weird Tales. Mason’s first novel, The Evolutionist, an unapologetic exploration of suburbia through the darkest of lenses, effectively changed the landscape of horror fiction and introduced her to the world as a force to be reckoned with. Her story “To the Marrow” will be featured in Weird Tales #364 in October, available in print, eBook, and audio.

Here’s what she had to say about her story creation process, diversity in the genre, what she is doing these days, and more.

L. MARIE WOOD: Were you a fan of Weird Tales magazine in your youth? If so, is there a specific author who stood out?

RENA MASON: I remember skip-reading an issue of Weird Tales when I was in my early teens but couldn’t relate to the stories or characters that I found very male-intensive, like Conan the Barbarian, so a lot of it went over my head. I enjoyed the works more as I got older because I think of them as appropriate for their time and they feel nostalgic, adventuresome, and fun. Of course reading them as an adult, I realized there was more there than the pulp, so it’s like I’d stumbled onto a trove of fiction I’d missed out on. I’d have to say Robert Bloch’s stories stay with me the most.

Weird Tales has an interesting history. While it is heralded for its contribution to speculative fiction, one of their mainstay contributors was controversial author H.P. Lovecraft. As an author of Thai-Chinese descent, what are your thoughts about the reboot of the magazine and its effort toward the inclusion of diverse voices?

RENA: I think any medium that puts an effort toward including diverse voices is fantastic. I appreciate what H.P. Lovecraft brought to the genre, but the people and worlds I want to read stories about take place across this Earth and beyond, which includes all races and then some, such as imagined peoples and places we authors create, like extraterrestrials, from single-celled lifeforms to human-like beings from different dimensions, universes, or times. Or they’re similar stories but told from the perspective of someone who is diverse, making them completely different and new. To me, stories written by diverse authors are like glimpses into a cultural variety of fears through literature, linking the reader and author in that shared fear. It is this basic and fundamental commonality that connects us no matter who we are or where we come from. Perhaps if I could’ve related to a character or two in the stories of the Weird Tales issue I’d read when I was younger, I’d have kept reading the magazine. It’s so important for people, especially younger people, to be able to see themselves in characters that they read. They need to see themselves reflected in a positive light and as main characters, not always the villains, the expendables, or the antagonists.

MARIE: Who do you credit as influencers to your writing and why?

RENA: Wow, there are so many. Scary stories have always been my favorites, but I didn’t start reading the genre seriously until I was around twelve, my first book being We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. I’d ordered it through Scholastic because I couldn’t get into all the horse story books the other girls my age were reading, and because the cover reminded me of myself, a young girl looking through a hole in a fence with long dark hair. But as I read it, I could absolutely relate to the characters. I grew up with two other sisters and we were latchkey kids who weren’t allowed to leave the yard until my mom came home from work late in the evenings. My childhood life was full of girls and women, and we were always taught to be suspicious of strangers, so the book took my imagination to dark places, which at the time, was very liberating. Then I started reading Poe and fell in love with all things Gothic, including classic works from the Brontë sisters, Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, and many others from the nineteenth century. I still consider Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black one of the scariest stories I’ve ever read. From there, I moved onto Stephen King, and then my love for horror really took off after reading The Books of Blood by Clive Barker. I mostly read a lot of history and science in my youth and teens. Discover magazine was one of them (I still have an online subscription to this day) and OMNI was the other. I used to buy OMNI for the non-fiction but hated wasting the rest of the magazine, so started reading the fiction. I credit OMNI and Ellen Datlow for all the great science fiction I read in my early teens, which also sparked my imagination and love for reading. Everything I listed above, and probably more, influenced my writing because I enjoyed reading it. From the Gothic to the non-fiction to the science fiction and horror, which is why much of my work is described as speculative fiction.

MARIE: You get an idea… you sit down to capture your thoughts… and then what? Are you an outliner or a pantser? Why?

RENA: Honestly, I’m a little bit of both. I get an idea, and then I think of the beginning, the middle, and the end. If the idea has all these components and is something I think would be a “good” story with a point, I’ll then think it all the way through before typing a single word. Sometimes this takes a few days or even months, often depending on the deadline. There’s nothing I hate more than wasting time. Whether I’m writing a novel or something shorter, I always jot down notes. I wouldn’t consider them outlines, legitimate outlines, as sometimes I’ll write them down with just a chapter number, and a brief description. For example: Chapter 23 – Boy dies.

There’s a lot to fill in with those two words, but it’s already been in my head for a while because I’ve thought it through. “Boy dies” is my trigger to get that part of the story out of my mind. I also let stories evolve on their own as I’m writing, which I’ve found allows for a lot of interesting subplots to develop. For some reason I always feel like my story is going to be too short, but then I end up making the word count or going over, and I think my way of “outlining,” and the notes I take, and thinking the story through from beginning to end before starting, really help with making the word requirements. Even with everything I’ve mentioned, there have been a couple of times where I haven’t been able to make a story come together. But with more time and thinking, I’ll be able to finish those. I think there are three.

MARIE: Short and long fiction are two different animals. Both require distinct skillsets beyond simple storytelling to produce a well-rounded piece. Which do you find most satisfying? Which is harder to finish and why?

RENA: I find writing novels the most satisfying because they encompass all my thoughts and ideas into one story, or a two to three novel series. Novels are also definitely harder for me to finish because of the revision process. I’ve been working on the revisions for my next novel for the last seven years, but in my defense, I was overextending myself with volunteer work and taking on too many commitments. Short stories also take a lot of my time, thinking them through, and are sometimes harder for me to pin down as far as what I want to express than a novel. Novelettes are a sweet spot for short fiction in my opinion. Novellas, for me, tend to wander into the novel arena, so if I tell myself I’m writing a novelette, it gives my short story idea a little more room. I have to trick my brain with word counts and deadlines.

MARIE: You admit to writing a kind of dark speculative fiction that mashes genres and I imagine that you enjoy the fluidity that allows, however, if you had to label yourself, which subgenre would you choose to describe your writing? Why?

RENA: I’m truly all over the place with genres and subgenres, but one thing I’m noticing more and more, and have been told often, is that a lot of my work is romantic. I was in complete denial of it for a long while, but I’m finally starting to “see” it in my work and understand its importance and what those elements bring to my stories. Another element I incorporate into my fiction is the term suburban. I know my mind dives into these subgenres because I’m familiar with them. Most of us know and have experienced romance and love and living at home. So if I’m able to take the familiar and turn it upside down, I feel I’ve got a story to tell. I’m typically known for being a horror and dark speculative fiction author because no matter what genre or subgenre I write, it’s going to be dark and have strong horror elements to it.

MARIE: Incorporating reality into your writing makes for a texture that purely fantastical tales do not possess. What do you find that you incorporate most into your stories – personalities, locales, scenarios, etc.? Why?

RENA: I’d like to say all of that, because together as a whole, that’s what makes a great story in my opinion. I’ll admit, though, that I typically start with and focus on the scenario in most cases, and then think of the people involved in that scenario, what kind of personalities they would have in order for them to learn and grow from the experiences I will put them through, and then lastly, I consider where the scenario would best be played out. I also like to incorporate some real history, facts, or science into a story, which I feel grounds my fiction and makes it more real, or at least possible.

MARIE: Fiction has always been challenged by an author’s ability to create imagery to sustain response and horror fiction ups the ante. How do you create visuals that linger in your readers’ minds long after they have put your book down?

RENA: I was an oncology, home health, and operating room nurse for many years, so when I’m writing graphic scenes in a story, I’ll put everything I remembered based on my real experiences into those, using all the senses, like smell and even taste, when I can. The same goes for many fears, too. I’ve been scuba diving for over thirty years and know what it is to feel claustrophobic, agoraphobic, nyctophobic, and thalassophobic, just to name a few, so I do my best to incorporate every detail of those memories into my work. I’ve traveled a lot, and have experienced many things, some considered extreme sports, and sometimes when I’m writing I close my eyes and re-live the memory. The feelings usually come back with reliving the experience. For me, it’s a matter of finding the right words most of the time, which is why I take a while with revising. When authors can relay personal experiences to readers, whether they’re physical or emotional, it’s a wonderful connect.

MARIE: You won the coveted Bram Stoker Award® for your debut novel, The Evolutionist. Tell me about the book and the experience.

RENA: Writing The Evolutionist was cathartic in that I’d moved from Las Vegas, Nevada to Olympia, Washington and had a lot to unload about the decade I’d lived in the desert of Sin City. The story’s about a suburban housewife who never really “fit in” among the other school and soccer moms. I never describe the main character’s appearance other than she has brown hair, but her “friends” are mostly blonde and plastic perfect. Strange things start happening to the MC, interfering with her daily routines, her family, and her friendships. She suffers from horrific nightmares that have nothing to do with her reality of life in the suburbs, and this scares her the most. She sees a psychiatrist but then her life unravels even faster until she comes to understand that she was never who she thought she was to begin with, and all the changes taking place in her life are out of her control. One of my author/educator friends, Bryan Thao Worra, told me that he’d used the book in a class as an example to teach Asian students how to write character metaphors. That was the highlight of writing The Evolutionist for me, but yeah, winning the Bram Stoker Award® for it in the First Novel category was pretty awesome, too.

MARIE: You are a member of several professional writing organizations, including Horror Writers Association, Mystery Writers of America, and International Thriller Writers. Likewise, you are active in industry conventions, speaking on panels that cover a wide range of topics under the speculative fiction umbrella. How do these interactions with writers and fans alike feed you emotionally and creatively?

RENA: Once I started attending conventions and retreats, I couldn’t stop. The energy I get from meeting authors, making new acquaintances, and chatting with friends and fans about everything under the sun—what I’m reading, what I’m working on, my life in general—is priceless. It’s both an intake and a release of “fresh air” and since the pandemic, I’ve never felt so alone in my creativity. The cancellations and postponements of this year’s conventions have been crippling in ways I can hardly express. It took me about a month to be able to write again. (Three looming deadlines also helped get me back into the writer’s chair.) But then I wrote three short stories I’m very happy with, and I started reading again as well. I’m going to get back to my novel revisions soon too. But I really and truly miss my friends and the friends I have yet to make. The hugs, the late-night discussions, cocktails, and laughter. Yeah, it’s been a sad 2020, especially because I’m a recluse and rarely leave the house other than to attend writer events. I try to attend new events every year, and last year I attended Bouchercon and MultiverseCon, and will most definitely be returning to both of those once traveling restrictions and the possibility of infection have diminished. Self-doubt is one of those terrible things that comes with the writing territory, so sitting at home and working and thinking gives me too much time for that beast to rear its head. It’s at the conventions and retreats where camaraderie and talking with fans reminds me why I write and makes it feel worthwhile.

MARIE: What are you working on now?

RENA: I’ve taken a hiatus from writing short stories so that I can finish the revisions on my next novel, which I’ll be querying to agents. Then I’m going to work on a couple screenplays before I get back to work on the revisions to the follow-up to my next novel release. Then I have another novel to write, and another one after that. I may also be tossing my hat into the ring as a co-editor. I try not to think too far ahead, but the ideas just keep coming.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

L. Marie Wood is an award-winning author and screenwriter. She is the recipient of the Golden Stake Award for her novel The Promise Keeper, as well as the Harold L. Brown Award for her screenplay Home Party. Her short story, "The Ever After" is part of the Bram Stoker Award® Finalist anthology Sycorax's Daughters. Wood is the Director of Curricula for the Diverse Writers and Artist of Speculative Fiction (DWASF) and the Director of Programming for the horror track at MultiverseCon. Wood’s novel, The Realm, a modern horror/sci-fi mash-up, will be released in September 2020 by Cedar Grove Publishing. – www.lmariewood.com Twitter: @LMariewood1

INTERVIEW: Lee Murray

By Geneve Flynn | Weird Tales talks with Lee Murray, whose story “The Good Wife” will appear in issue #364.

By Geneve Flynn

Lee Murray, award-winning New Zealand author and editor, talks about weird fiction, her latest weird tale, and the strange and mythic world of the land of the long white cloud. Lee’s story “The Good Wife” will appear in issue #364 of Weird Tales.

GENEVE FLYNN: Thanks for chatting with me today, Lee. We recently co-edited a horror anthology that was brimming with the uncanny, and your story “The Good Wife” feels like a very natural extension of that experience. What does weird fiction mean to you, and why do you think it’s had such lasting appeal?

LEE MURRAY: Weird fiction has a universal appeal because there is a supernatural and spiritual quality to it, a sense of the uncanny, and the exploration of those aspects offers us a deeper understanding of the complexities of our world. Jeff VanderMeer, who co-edited The Weird with former Weird Tales editor Ann VanderMeer, wrote in 2014, “There’s a power and weight to this type of fiction, which fascinates by presenting a dark mystery beyond our ken and engaging the subconscious. Just as in real life, things don’t always quite add up, the narrative isn’t quite what we expected, and in that space we discover some of the most powerful evocations of what it means to be human or inhuman.” (Jeff VanderMeer, “The Uncanny Power of Weird Fiction,” Atlantic, Oct 30, 2014.)

GF: Weird Tales has been a seminal part of the speculative fiction landscape since 1923, with bestselling authors, including Stephen King, citing it as an important influence. When did you first encounter the magazine?

LM: How did I first hear of the magazine? I vaguely remember seeing Weird Tales on shelves in my local library in New Zealand in the ’70s. Too young to borrow them, I recall the vibrant, outlandish covers, which have gone on to symbolise the magazine. But your question got me thinking: has the magazine appeared widely here in New Zealand over the past century, and have any of my compatriots appeared on its pages? If so, wouldn’t it be wonderful to highlight those stories and their authors?

I did some browsing, discovering Terence Hanley’s excellent contributor site, Tellers of Weird Tales, but was unable to find any familiar names. I contacted Hanley to see if he had additional information, and he kindly replied, “I don’t know of any author who contributed to Weird Tales from 1923 to 1974 who came from New Zealand. That’s not to say that there wasn’t one, but I don’t know of any. I won’t know until I have gone through the entire list and have written about all of them, but even then, there are going to be several authors about whom nothing is known, including their real names. There could be a New Zealander hiding in there somewhere and we may never know.” Hanley mentioned New Zealand indexer Thomas G. L. Cockcroft as proof that people (or at least one person) in New Zealand read Weird Tales during the magazine’s history, but could shed no light on whether those copies might have been purchased at the newsstand, by subscription, or some other means.

That conversation had me bounding off down a research rabbit hole, contacting publisher John Harlacher, who knew of no New Zealand contributors either. Who were the likely suspects? I rattled off some names including Maurice Gee, Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Katherine Mansfield, and Janet Frame. Perhaps Arthur C. Clarke finalist Phillip Mann had appeared in a back issue listed as a British author? I contacted Mann, a personal friend, who didn’t recall ever submitting work to the magazine.

Clearly, I needed to dig deeper; I emailed New Zealand fan historian, Ross Temple. Temple added Robin Hyde to my list of possible Kiwi contributors, and recommended I contact Murray MacLachlan, a friend of the archivist Thomas Cockcroft, who was now based in Melbourne and still involved in fandom. Temple had no idea how to contact him, but weird folk have weird ways, so I sent out a couple of text messages to colleagues, and within a day MacLachlan had contacted me. Yes, he had some of Cockcroft’s bibliographies, given to him when interviewing Cockcroft for his notes on New Zealand science fiction and fantasy. MacLachlan spoke fondly of Cockcroft as a bibliographer of some note, the larger bibliographies self-published in 1962, 1964, and 1970, and distributed through a US agent based in Staten Island, helped by word of mouth through the Weird Tales community. MacLachlan said he’d check his archives, but from memory he didn’t know of any New Zealand authors appearing in the magazine.

The trail might have stopped there, but MacLachlan suggested I contact another friend of Cockcroft’s, Rowan Gibbs of Smiths Books in Wellington, since Gibbs had also inherited some of Cockcroft’s bibliographies.

I made the call just before lunch. Gibbs answered on the first ringtone and we had a lovely conversation. He knew of no other New Zealander to appear in the magazine either, although he pointed out that Cockcroft’s interest was mainly in the American contributors and that he had corresponded with several of them personally, including Forrest Ackerman and his contemporaries. This point was confirmed by MacLachlan who said Cockcroft had been a member of a US-based fantasy amateur press association, which meant he was in regular mail correspondence with fans such as Donald Wollheim. Both MacLachlan and Gibbs expressed regret that the Cockcroft family had disposed of Thomas’s personal correspondence when he was medically retired to a rest home after an illness. The family did retain Cockcroft’s Weird Tales collection, but Gibbs said the magazines were in rather poor repair. However, as a bookseller, he was able to confirm that Weird Tales was frequently available in various bookstores in New Zealand through the 1930s and up until the war, and that Cockcroft had bought his copies locally. During the war years, supplies were patchy, with New Zealand’s book stocks sourced mainly from Britain, but US magazines tended to get through.

I emailed Terence Hanley with the names suggested by Gibbs: Cedric Centiplay was a possibility, or one of his many aliases. My Kiwi horror colleague, William Cook, had suggested Paul Haines and Tamsyn Muir, so I forwarded those names to Hanley, too.

Hanley replied expressing his dismay about the loss of important legacies such as Thomas Cockcroft’s. It’s the reason gaps exist in archivists’ knowledge about Weird Tales. Something similar had happened to the bibliographies of Leo Margulies, who owned the Weird Tales property from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s. Margulies purportedly kept files and correspondence he’d inherited in his garage, and they’d become infested with insects and later thrown away.

But Hanley also had news, neatly ruling out Centiplay, Haines, and Muir based on entries in the The Collector’s Index to Weird Tales by Sheldon Jaffery and Fred Cook (1985), although he pointed out that the book only covered issues to Summer 1983. Hanley knew of no other index to Weird Tales issues released after that date. He noted that he had consulted the Internet Speculative Fiction Database indexes, but it would be a long and involved process to search the authors in each issue to pinpoint any New Zealanders.

Hanley had heard from Randal A. Everts, who’s been researching contributors to Weird Tales since the 1960s. Everts considered Denis Plimmer (1914-1981), might have been a New Zealander, but subsequent research revealed he was in fact born in Melbourne, Australia, although he may have lived in or visited New Zealand, his father’s native country, as a child. (Plimmer’s particular fame was that he and his American wife, Charlotte, were co-authors of a key article on J.R.R. Tolkien.)

“Denis Plimmer’s name is the only one offered by Mr. Everts,” wrote Hanley. “I would say that if he doesn’t know of any New Zealanders who contributed to Weird Tales, then there probably wasn’t one. It seems pretty safe to say that you will be the first!”

So, there it is: unless there is a reader out there who can point us to another, I may be the very first New Zealander to appear on the pages of Weird Tales. That fact seems uncanny and fantastic in itself, since there are many far more accomplished writers among my compatriots, both living and dead. My knees have barely stopped shaking since I received Terence Hanley’s last email. I do feel a little sad that it has taken this long to bring our Kiwi weirdness to the magazine, but I hope it is a sign of things to come.

GF: Congratulations on being a pioneer! Here’s to much more weirdness from around the world. Speaking of which, who are your favourite weird fiction authors and which stories have resonated with you the most?

LM: Well, Poe, naturally. “The Telltale Heart”, which Stephen King describes as “a persuasive story of lunacy,” has been a favourite of mine since I first read it as a schoolgirl, bearing out King’s observation that the author “foresaw the darkness of generations far beyond his own.” The French poet Charles Baudelaire, a contemporary of Poe and credited for translating much of his work, is another favourite. Lovecraft. Conan Doyle. Mary Shelley. King himself. It’s a long list.

Lee at one of Poe’s gravesites, in Baltimore

GF: Yes, there are many authors who have written brilliantly in this genre, and many, many stories. Which leads to my next question: what weird fiction cliché would you sacrifice to the unknowable gods?

LM: Perhaps, it is time for predominantly Western tropes to make way for more global representations, and reinterpretations, in bizarro fiction. Asian interpretations. Pasifika stories. Tales from the LGBTQ community. I’d like to see stories which twist current concerns and force us to look at them differently: weird tales on the recent devastating bushfires, the proliferation of the Asian giant hornet, new takes on AI. I expect the editorial leadership of Jonathan Maberry will result in renewed vigour. Already, in just two issues, we’re seeing him expand the magazine’s reach to include fresh voices and perspectives. And it makes sense, because weird fiction seeks to subvert traditional interpretations: what better way to do that than to throw open the doors to new voices?

GF: That was certainly the zeitgeist at the recent WorldCon in New Zealand. Readers, editors and publishers were vocal in their desire for fresh voices. Your tale “The Good Wife” presents a wonderfully unique perspective. Can you tell me what inspired the story, and what it was like writing for the magazine?

LM: “The Good Wife” was inspired partly from my own heritage as a third-generation Chinese New Zealander, and also the result of some research I’d uncovered around the differences between European and Chinese mining techniques. The story is set in the 1800s, in Arrowtown, at the heart of New Zealand’s goldfields, where a dutiful Chinese wife, known only as Second-Daughter, negotiates with a taniwha—a supernatural serpent-dragon of Māori mythology—for the life of her feckless miner husband. It’s a grimdark Chinese-New Zealand fairy tale imbued with themes of duty and ambition, which juxtaposes Chinese and Māori notions of the mythical taniwha-dragon. I hoped to highlight the Chinese diaspora in New Zealand and the harshness of life in those early mining communities. I squeezed in a mention of our gasp-worthy wētā-cricket as well. As far as writing for the magazine goes, my imposter syndrome was out in full force. Even now, with the contract neatly filed away, it still feels surreal.

GF: Speaking of surreal, the real and mythical landscapes of New Zealand often feature in your stories. How does this fit into the genre of weird fiction?

LM: If weird fiction invokes a sense of the numinous, then New Zealand’s landscape makes for the perfect backdrop. Aotearoa is a brutal yet beautiful place where wairua-spirits walk close to the veil, as American William Schafer pointed out in his book Mapping the Godzone (1998): “A common cultural link between Pākehā and Māori is a belief in the hauntedness of the landscape, the sense that Aotearoa New Zealand is a land of sinister and unseen forces, of imminent (and immanent) threat, of the undead or revenant spirits.” In fact, the Māori term tipua refers to demonic uncanny things from our local landscape. It’s part of the fabric of our lives, as my Path of Ra co-author, Dan Rabarts (Ngāti Porou), states: “Our gods and ghosts are primeval, a constant presence in the backs of our minds, both bloodthirsty and mischievous. Turn your back, deny them for even a moment, and they don’t miss an opportunity to remind us they’re there, and that they don’t like us. New Zealand is full of ghosts, all the time…” (Dan Rabarts & Lee Murray, “Underworld Gothic,” Halloween Haunts, HWA, October, 2017). Like I said, the perfect backdrop.

GF: You’ve mentored many writers, and developed and funded programs to support new writers, what’s the best piece of advice you could give to someone starting out?

LM: There is so much advice, isn’t there, and everyone’s path is different, especially given that the publishing landscape is changing so rapidly with new opportunities evolving every day. Nevertheless, there are some indisputable truths, like write the story you want to read; write the best story you can; revise; rewrite; send it out; write another; read a lot; read some more; read more widely; keep writing… But overall, I want to say that writing is hard, so mostly people should always remember to be kind.

GF: Weird Tales has undergone many iterations and continues to evolve. What are your thoughts on the magazine’s new direction?

LM: I’m excited to see the diversity that will undoubtedly come from Maberry’s stewardship, and the vitality those authors will lend the magazine. I expect Maberry’s own versatility as a writer of multiple genres and media will influence what readers will see in future issues. He’s not afraid to pull up a chair for newer writers, to take a risk. Me, for example. I hadn’t yet come across Marguerite Reed, who appears in issue #364, and I’m looking forward to discovering her work. Of course, Weird Tales has a great team with people like editor James Aquilone behind the scenes polishing the work to obsidian. I think the future looks dark at Weird Tales, and in a good way!

GF: And finally, can you tell us about your latest projects, and what you’re working on next?

LM: Thank you for asking, Geneve. Despite the pandemic, my publishers have been working hard to push my weird work into the world. In July, Things in the Well Australia released my debut short story collection, Grotesque: Monster Stories, and in September, Omnium Gatherum released Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women, an anthology by Southeast Asian horror writers that you and I have edited, featuring some of our favourite writers of weird fiction, including three-time Bram Stoker Award®-winner Rena Mason, who also appears in issue #364. I’m currently working on a poetry collection in a spin-off to the work we started with Black Cranes on the Asian diaspora in horror. And finally, in November, Raw Dog Screaming Press will release Blood of the Sun, the final installment in the Path of Ra supernatural crime-noir series I write with my Kiwi colleague Dan Rabarts, which, rather fittingly, ends with a spectacular showdown in the volcanic crater of Auckland’s Maungawhau (Mount Eden) as the Earth switches magnetic poles.

About Lee Murray

Lee is a multi-award-winning writer and editor of science fiction, fantasy, and horror (Sir Julius Vogel, Australian Shadows) and a three-time Bram Stoker Award® nominee. Her works include the Taine McKenna military thrillers, and supernatural crime-noir series The Path of Ra, co-written with Dan Rabarts, short story collection, Grotesque: Monster Stories, as well as several books for children. She is proud to have edited fifteen speculative works, Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women (co-edited with Geneve Flynn) is the most recent. She is the co-founder of Young New Zealand Writers and the Wright-Murray Residency for Speculative Fiction Writers, and HWA Mentor of the Year for 2019. In February 2020, Lee was made an Honorary Literary Fellow in the New Zealand Society of Authors Waitangi Day Honours. Lee lives in New Zealand’s sunny Bay of Plenty where she dreams up stories from her office overlooking a cow paddock. Read more at www.leemurray.info

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Geneve Flynn is a freelance editor from Australia who specialises in speculative fiction. She has two psychology degrees and has only ever used them for nefarious purposes. She has been a judge for a key Australian horror award and a submissions reader for a leading Australian speculative fiction magazine. Her horror short stories have been published in various markets, including Flame Tree Publishing, Things in the Well, and the Tales to Terrify podcast. She is a professional member of the Institute of Professional Editors and teaches creative writing courses with Brisbane Writers Workshop.

She loves tales that unsettle, all things writerly, and B-grade action movies. If that sounds like you, check out her website at www.geneveflynn.com.au.

INTERVIEW: Marguerite Reed

By Brian Trent | Weird Tales talks with Marguerite Reed, whose story “The Beguiled Grave” appears in Issue #364.

By Brian Trent

BRIAN TRENT: Can you give us a teaser trailer of “The Beguiled Grave”?

MARGUERITE REED: Varka, the main character, has been raised from the dead and uses her peculiar talents to assist an incognito ruler. There are some dead bodies, some sketchy magic, spooky stuff. Oh, and dogs.

BRIAN TRENT: How familiar were you with Weird Tales’ classic run prior to this sale?

MARGUERITE REED: To be honest, I wasn’t terribly familiar with the stories themselves, just with the enormous stature of the magazine itself in the annals of speculative fiction history. I am pretty tickled that Weird Tales was the first home of CL Moore, whose sword and sorcery female protagonist Jirel of Joiry made her appearance eighty-six years ago. I remember reading those stories in my teens.

BRIAN TRENT: Weird Tales’ history covers a lot of fantasy ground, ranging from Robert E. Howard’s Conan tales to C.L. Moore’s interplanetary adventurer Northwest Smith to H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. What decided you on your own subject, style, and setting for this story?

MARGUERITE REED: Of course I wanted to write a female main character. I wanted to play with someone who could hold her own with Howard's Conan or Karl Edward Wagner's Kane--yet I didn't want to offer a Red Sonja copy. I didn’t want to trot out the tired old image of the FFT—the Fighting Fornication Toy. You know—the hot chick accessorized with corset armor and a rapier. Instead setting the fantasy in a mythic 'barbarian age,' of rude yet noble warriors pitted against corrupt civilization (a la Goths or Celts vs. Rome), or in an idealized 12th century with knights and courtly love, I wanted to explore a fantasy set in an approximation of Eastern Europe during the truly dire 15th and 16th centuries. After all, this is the era of some truly horrific and creepy stuff, the era of Gilles de Rais, Vlad Țepeș, Peter Stumpp, and Erzsébet Báthory, as well as the haunting artwork of Bosch and Bruegel. Given all these ingredients, I wanted to try to combine sword and sorcery with horror.

BRIAN TRENT: What draws you to speculative fiction as a writer? What started the attraction?

MARGUERITE REED: It was my favorite genre as a child. When at 13 I decided that I was going to be a writer, it was the only genre that occurred to me. I suppose because writing is a form of vicarious living, and I wanted to be Brünhild, I wanted to be Eilonwy and Éowyn and all the girls who rode a horse and swung a sword. Not having a horse, and not being of an athletic disposition, writing was a way into that.

BRIAN TRENT: From a writing perspective, what initially kicks off a story for you—an idea for a character, a dream, a setting, an action sequence?

MARGUERITE REED: A lot of times it’s art. Are you familiar with the drawing “A Paladin In Hell” by David C. Sutherland III? It’s on page 23 of the D&D Player’s Handbook published in 1978. That image inspired the character of Varka for me. I also did a lot of staring at Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Triumph of Death.” It’s a painting he did around the middle of the sixteenth century, and it’s always loomed in my mind as one of the greatest depictions of despair on a grand scale ever. Another painting that haunted me is one done by the late Zdzisław Beksiński’, known as “The Night Creeper.”

BRIAN TRENT: What kind of research or other kinds of preparation (idea notebooks, outlines, etc) did you do for this story?

MARGUERITE REED: Imagine writing in a genre where research isn’t a primary concern! I wonder what that’s like? I can tell you I learned a lot more about crucifixion than I did before. I’m also struggling through the late Medieval/Renaissance-era eastern Europe—the milieu there is very different from what I’m familiar with in western Europe. I don’t want to inflict my research on my readers, but I do want the fiction to feel grounded.

BRIAN TRENT: “The Beguiled Grave” reads as the start of an epic saga with fascinating characters and a very rich setting. Might we see stories on the further exploits of Varka in the future?

MARGUERITE REED: I certainly hope so! I've always enjoyed serial characters. Varka and her world have a lot of aspects I'd like to explore. But it does depend on whether or not the audience agrees with you and what the market will bear, doesn't it? It would be an incredible rush—and honor—to be able to continue with Varka in this incarnation of Weird Tales.

BRIAN TRENT: How do you feel about Weird Tales’ revival?

MARGUERITE REED: I’m excited about it. It’s always great for fans of speculative fiction to be able to get their eyeballs on another source for stories. I think we’re on the upward swell of a great new wave of speculative short fiction, despite the publishing horrors that emerged from the recession of 2008-2009. Knock on wood, anyway.

BRIAN TRENT: What’s next for you? Are you working on anything that you’d like to share?

MARGUERITE REED: I'm working on some science fiction at the moment. And more Varka, of course, both in short and long form!

BRIAN TRENT: Where can fans find you online?

MARGUERITE REED: On Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/marguerite.reed.1232 and Twitter at @Marguer43001568

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brian Trent’s speculative fiction appears regularly in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Analog, The Year’s Best Military and Adventure SF, and more. His novel Ten Thousand Thunders is available from Flame Tree Press, and his website is http://www.briantrent.com/

INTERVIEW: Gregory Frost

By Jon McGoran | Weird Tales talks with Gregory Frost, whose story “Ellende” appears in Issue #364.

By Jon McGoran

JON McGORAN: What was the inspiration for your story “Ellende”?

GREGORY FROST: It’s . . . complicated. Let me see if I can enumerate these things in sequential order. My grandparents owned two large cabins on Big Sandy Lake in northern Minnesota. They always stayed in one, and my family, when we came up in the summer, stayed in the other one. We fished, skied, swam, and drove further north, right to the Canadian border one year. So, there was that. Then, back in my late teens I became a huge reader of Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith and other Arkham House authors, thanks to a college art professor of mine, Gaylord Torrence, who got me to read Lovecraft. The summer after my second year of college, I packed up my typewriter, paper, and a girlfriend and drove to my grandparents’ cabin with the intention of writing a novel—about which, I should add, I knew sweet FA (this novel proved to be 74 pages long and it lives in a box, which is where it belongs). I also tried writing something Lovecraftian set on the lake, with ancient structures on one of the tiny island; it mixed Cthulhian elements with Ojibwe lore, and it was pretty terrible, but the idea of relocating Lovecraft’s haunted New England resonance to the woods of Minnesota never really went away. Jonathan Maberry’s invitation to write a story for the new incarnation of the magazine gave that desire a voice.

JON McGORAN: When does “Ellende” take place? Why did you choose that period, and how important is that to the story?

GREGORY FROST: It’s set around 1950. To an extent I landed there because the car, the Packard Club Coupe, is virtually identical to my grandfather’s Packard, right down to the cigar smell of the interior. It was a time when you had these odd cabin properties sprinkled around all the lakes up there, but semi-isolated. Everything wasn’t built up. Although it’s earlier than my childhood experience of it, the setting really is the northern Minnesota of my childhood. What cemented it was giving the two main characters the first names of my grandparents. My grandfather was a doctor who, family legend has it, had delivered half the babies in Des Moines, Iowa. He and my grandmother are definitely not the Floyd and Jessie of the story, but their names felt exactly right. One of my early readers, who didn’t know any of this, said that she thought the names perfectly evoked the period for her. So I think that worked both for me writing it and for the reader encountering the story.

JON McGORAN: Is this a style and genre you often write, or is this more of a departure for you?

GREGORY FROST: I think I write strange fiction, however you care to define that. I try to flex all over the place, though, in terms of voice. The last story I wrote before this, which just came out in Asimov’s Magazine, is a first-person sf narrative told by a character living in a trailer park in a small town in Iowa. So it does seem I have suddenly started writing “Iowa” stories. I don’t know yet if this is a departure or a direction.

JON McGORAN: What do you think of as your native genre?

GREGORY FROST: Do I have to pick? I have always loved horror fiction, by which I generally mean darker, troubling, discomfiting fiction—everything from Shirley Jackson to Nathan Ballingrud to Livia Llewellyn. My first published story was about the last five days in the life of Edgar Allan Poe. But the story after that was a science fiction story set in a spaceship trapped above the event horizon of a black hole. And the one after that was about a magazine cover artist living in an apartment complex where something has moved into the communal trash dumpster. So, again, I think my native genre is strange or weird. Fortunately, that comes in lots of flavors.

JON McGORAN: Did you write the story specifically for Weird Tales, and if so, how did knowing that’s where it would be published affect your writing of it?

GREGORY FROST: I did write this specifically for Weird Tales. So I knew I was dipping my pen into the Lovecraft inkwell (I write longhand, beware!). I’d recently read The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle and really admired how he shredded the racism of “The Horror at Red Hook.” And I thought, okay, I can’t do that, but I can sort of confront Lovecraft’s misogyny and see where it takes me. So, knowing this was set in this time, and who these two people were by name, and that vague beginning place, I just started writing. This became one of those stories where all the way along I probably came to each scene maybe a heartbeat ahead of the reader.

JON McGORAN: Does having a story in the new Weird Tales carry any special meaning for you?

GREGORY FROST: Oh, absolutely. This is the second story I’ve sold to WT. (The first one—maybe two magazine incarnations ago—called “So Coldly Sweet, So Deadly Fair,” was about Abraham Van Helsing’s very first encounter with a vampire, and the death of his son and loss of his wife, both of which are mentioned in passing in Dracula.) But also, as I said back at the start, my teen years were fairly steeped in authors who had published in Weird Tales in the 1930s and ’40s, and writers such as Ray Russell, and Charles Beaumont (who ultimately adapted Lovecraft’s The Case of Charles Dexter Ward for film). So being in Weird Tales definitely feels right.

JON McGORAN: What is your earliest or most vivid memory of Weird Tales magazine?

GREGORY FROST: I think my first actual memory of encountering Weird Tales directly was via the anthologies with that title that Lin Carter edited in the early 1980s, which mixed the Robert E. Howards and August Derleths with younger writers like Tanith Lee and Steve Rasnic Tem. Somewhere I think I still have those paperbacks hiding away in a box.

JON McGORAN: Can you tell us about a particular Weird Tales story that stands out in your mind, or that was particularly influential for you?

GREGORY FROST: It might well be Robert Bloch’s “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” When I read it now, the resolution seems obvious, but I remember being astonished by the story at the time. But there are also Manly Wade Wellman stories, some of which appeared first in WT, and which take on special meaning for me, as I got to know him in the early 1980s when I lived in North Carolina. (Author David Drake used to throw pig-picking parties, a kind of large nighttime barbecue, drawing up a group of more-or-less local writers. We all sat around David’s property, drinking beer; Manly, who was still going strong when I first met him, displayed that storyteller’s brilliance in talking around the fire late into the night.)

JON McGORAN: What makes Weird Tales special to you?

GREGORY FROST: I think it’s the magazine equivalent of Christopher Lee as Dracula. Every time we are certain he’s been killed and cannot possibly come back, there he is again in yet another sequel. Weird Tales is like that—there is always a new generation hungry for the weird, dark, and unsettling. And there seems to be enough to go around.

JON McGORAN: Where can fans find you online?

GREGORY FROST:

Website: https://gregoryfrost.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/gregory.frost1

Twitter: @gregory_frost

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jon McGoran is the author of ten novels for adults and young adults, including the award-winning YA science fiction thrillers Spliced, Splintered and Spiked, and the acclaimed science thrillers Drift, Deadout, and Dust Up. He has also written numerous short stories. He is a freelance writer, developmental editor, writing coach, and cohost of The Liars Club Oddcast, a podcast about writing and creativity.

INTERVIEW: Linda D. Addison & Alessandro Manzetti

By Jezzy Wolfe | Weird Tales caught up with the pair for a discussion about their work together, and the challenges of poetry collaborations.

By Jezzy Wolfe

The unexpected collaboration of Linda D. Addison and Alessandro Manzetti have gifted us with two impressive poetry collections, The Place of Broken Things, and The Raven, Il Corvos. Addison’s charming lyricism paired with the sharp edge of Manzetti’s gritty prose make for luscious amalgamations of brutal beauty and dark decadence. Of course, each poet is already a veritable legend on their own.

Linda Addison is a five-time Bram Stoker award winning author and poet, and the first African American recipient of a Stoker. She has had over 350 poems, stories, and articles published, and received the HWA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018. She is the poetry editor for Space & Time magazine, as well as a frequent honorable mention in the Year’s Best Horror and Fantasy, as well as the Year’s Best Science Fiction. With a lengthy list of notable awards and nominations, she is one of the most respected and inspirational authors of our time.

Likewise, Alessandro Manzetti also boasts an impressive catalog of awards and accomplishments. He is a two-time Bram Stoker Award Winning author, as well as a SFPA Elgin Award Winner, in addition to countless nominations for various Bram Stoker, Elgin, Rhysling, and Splatterpunk awards. He has received at least 20 honorable mentions in The Year’s Best Horror, and in 2017 he won the HWA award for specialty presses as the CEO for Independent Legions Press. His work can be found in publications all over the US, the UK, and Italy. Alessandro has also translated works from some of the biggest names in horror – Richard Laymon, Poppy Z. Brite, Edward Lee, Graham Masterton, H.P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allen Poe, to name but a few.

Weird Tales Magazine features poems by Manzetti and Addison, The Canal, and The Last War, respectively. We caught up with the pair for a discussion about their work together, and the challenges of poetry collaborations.

JEZZY WOLFE: When did you first become a fan of Weird Tales? How old were you when you first read the magazine?

LINDA ADDISON: I discovered Weird Tales when I worked a summer job on campus in college in the 1970’s. I rented a room in a fraternity house on campus and they had piles of old books and magazines in the attic. It was like discovering a hidden treasure.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: My first time with Weird Tales was in in the early 1990s, discovered some copies in a comic book store in Rome. The owner of that store was a great fan, and showed me his collection. I was immediately fascinated by the fantastic vintage cover arts, and bought a couple of issues.

JEZZY WOLFE: Weird Tales launched the careers of a lot of landmark authors, such as HP Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, CL Moore, etc. Were any of them influences on your writing?

LINDA ADDISON: Some of my influences published in Weird Tales are: Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Harlan Ellison, and Stephen King.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: In addition to Lovecraft, I should mention Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber and Richard Matheson.

JEZZY WOLFE: Do you focus on creating implicitly horror-themed poetry? If not, do you find it more or less challenging than writing in broader poetic themes?

LINDA ADDISON: I rarely decide what the theme of a poem is when I write, unless I’m writing for a particular publication/theme. For example, when I wrote Poe-inspired poetry for Alessandro (The Raven, IL Corvos) I re-read Poe’s poetry (Poe was a major influence from my teen years) and let the Muse/inspiration take over. Often my poetry does give voice to shadowy themes because my heart responds to what causes others pain and suppresses them.

I’m also drawn to broader poetic themes because I’m always reaching for a wider understanding of humanity on Earth and in the Universe.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: Usually my poetry works are focused on the dark side, using a 'street' and 'expressionist' style; I think they can be defined as horror, weird, and magic realism themed. But labels are not so important, and no theme is more challenging than others. The point is to be open to all noise, screams and music you can hear reverberating at full volume inside your soul, while you’re observing and living the modern world.

JEZZY WOLFE: Do you take much inspiration from current events, or do you rely on classic horror themes and elements as you are writing?

LINDA ADDISON: Every thing inspires me, the news, everything I see, hear, my reactions to the world around me, today and the past. I grew up watching B horror movies on TV and loved them. They are as much an inspiration as new movies.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: I'm inspired by the world around me, by the stories I've come across, directly or indirectly; bunches of hard days and nights are my muses and guides, and quite often they appear like vivid, dark daydreaming. No classic horror themes, simply real-life themes, which can be worse.

JEZZY WOLFE: Are you influenced by past poets, and who would you say are your biggest poetic influences?

LINDA ADDISON: I read everyone I could get my hands on growing up, so that’s a long list, but some at the top of the list are through high school, not all poets, but some because of the poetry in their writing: Poe, Baldwin, Kafka, Shakespeare, Langston Hughes, Cheever, and Toni Morrison. I loved to read out loud when alone. I was completely in love with words and the music I felt in them. In retrospect, I imagine many of these writers/poets cadence influenced my writing, helped me discover my own rhythm.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: The list is long also for me, I read poetry since my adolescence, falling in love with French poets, especially Verlaine, Rimbaud and Baudelaire, and other big names like Alighieri, Blake, Keats, Whitman, Eliot, Thomas and many others. After growing up, and a long period during which I was greatly fascinated by surrealists (see Apollinaire, Éluard, Desnos) I discovered a new world thanks to beat poets, my heroes, Ginsberg, Corso and their crazy friends. I think all this imaginary route guided me, one piece at a time, to find my style, my own vision.

JEZZY WOLFE: You have worked together on two collections of poetry, The Place of Broken Things, as well as The Raven, IL Corvos. What challenges can one expect when collaborating on poetry, and how did you circumvent them?

LINDA ADDISON: For me, a big part of making collaborations work smoothly is the ability for each author to be open to input from the other. Alessandro and I began with a great amount of respect and love of each other’s work. We worked without ego, our main purpose was to create the best work possible for our book. As we shared pieces of poems, we each could decide to play in building the poem together or not (in which case, the originator would finish the poem). In the end, our book was a third collaborative poems, a third poems by each of us separately. Staying open allowed us to inspire each other to write work that was unique to our partnership.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: I agree with Linda, we worked together and found a unique voice, giving life to a 'third poet', playing the same songs; it was a fantastic experience. To do that you need the right traveling companion, and to get over yourself to follow the music, the words, the images of something new, over there, someplace where you've never been, where our four legs and two hearts brought us. It's a matter to put aside your ego, since we think our ideas, visions and styles are so important and absolute. This is the challenge of a collaboration.

JEZZY WOLFE: The new Weird Tales is moving in a different direction — focusing on inclusion and unique voices of all kinds. What was your reaction when you heard about that?

LINDA ADDISON: I was so excited to hear about this change and the fact that Jonathan Maberry was the editorial director. There are so many wonderful voices out there who aren’t the traditional names. Adding new voices to the mix will create fantastic energy for readers and the magazine, as well as exposure for authors who may not have been read by a wider audience.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: It's the right way, and I was excited when Jonathan explained to me the new direction. We need to hear new voices, often outdone by mass market's 'orchestra'; we have so many talented writers out there. It will be a new blood for the genre, and a righteous and creative rebirth for Weird Tales.

JEZZY WOLFE: Do you feel that the industry is making strong enough efforts to increase publication opportunities for writers of color, and other marginalized groups? What would you like to see more of, going forward?

LINDA ADDISON: There are efforts being made now, but there’s more work to be done. Excellent work is being done by people like Jonathan Maberry with Weird Tales, and Christopher Golden & James A. Moore editors of The Twisted Book of Shadows anthology and others who are making a conscious effort to reach out to underrepresented communities, to include them in their editorial group. Professional writing organizations, like HWA’s column The Seers Table, in their monthly newsletter to introduce membership to writers outside the usual.

More has to be done with including more diversity in the levels of editorial staff. It takes extra effort to make sure publications are inclusive. Doing things the same way, will produce the same results. The horror community has called out publishers who create anthologies that don’t include the usual excluded groups, because they weren’t mindful about their process.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: Industry is making something about it, but it can do better than that. I would like to see many more works of writers of color, especially in the horror field; editors and publishers should make a more serious commitment about that, reviewing their plans, working harder in scouting and submissions, and including a new young open-minded staff. I don't forget marginalized groups and underrepresented communities, but considering the many initiatives luckily carried on in the last 3 to 4 years, I think the main problem for now still involves the writers of colors.

JEZZY WOLFE: What is the best piece of advice you have received in the course of your writing career?

LINDA ADDISON: Read widely, not just in my area of interest. Keep a journal (on paper, computer or phone) of any bits and pieces that come to mind. Try to set a schedule for writing, even if only for five minutes a day. Let first drafts be what comes through, without judgement or editing, just write from beginning to the end. Be open to try new forms.

Re-write as well as I can, if possible get feedback, then submit to appropriate markets, after reading the submission guidelines carefully.

Repeat.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: Don't be afraid, write your book as if it's the last thing of your life, each time, without thinking of tomorrow. You're not a salesman, don't worry about the numbers. Market expectations are bad company.

JEZZY WOLFE: What advice do you have for young poets looking to place their work in today’s professional publications?

LINDA ADDISON: For each piece I finished, I make a list of at least three possible markets. The list starts with the top markets in pay, prestige or personal interest. When I first sent my poems out years ago, I loved Charlee Jacob work and would send my poems to places that she was published in. Once a poem was as good as I could make it, I keep circulating it. If a poem comes back and I see how to make it better, make the change(s), send it out and work on something new.

It’s not that rejections aren’t upsetting, it’s that feelings aren’t reality. Feel bad, but keep sending your work out. We aren’t the best judge of our own work.

When reading a market submission, pay attention to the subjects they want or don’t want, the limits of number of lines or words they define, etc.

ALLESANDRO MANZETTI: I have only one suggestion: Read.